The best online fitness resource you'll ever need. We filter out the BS to ensure you meet your health and fitness goals!

The best online fitness resource you'll ever need. We filter out the BS to ensure you meet your health and fitness goals!

Want to be more attractive? Have wide shoulders with these middle deltoid exercises.

Science proves that guys with wide shoulders are more attractive. A 2008 study published in the Review of General Psychology (Gallup and Frederick) spells out things that make a guy sexier, and one of those is the Shoulder to Hip (STH) ratio. Bigger shoulders, narrow waist.

What’s the best way to get your shoulders wider faster?

We’re going to share our top three middle deltoid exercises that promise to grow deltoid muscle based on anatomy and physics.

We’ll also break down other popular shoulder exercises and explain why they’re not our top choices, and share why some others don’t live up to their reputations.

The medial deltoids are the muscles that add that cannonball look to the shoulder. Growing them is the fastest way to get bigger, broader shoulders, even if nature cheated you, and left you with a narrow bone structure.

Keep in mind that the medial deltoid is responsible for one thing: moving the arm straight out to the side. It doesn’t rotate the shoulder or move the arm backward, turn the hand, or bend the elbow.

The design of the medial delt is why we’ll focus on variations of the single isolation exercise that develops it best: the side lateral.

This is the single best exercise to isolate the middle deltoid muscle.

The Standing Cable Side Lateral takes very little imagination to figure out, especially if you’ve got experience with resistance training.

How to do it:

In other words…

Standing Cable Side Laterals are a lot like a one-arm dumbbell side lateral, only better. Here are three reasons why.

You can optimize the Standing Cable Side Lateral to make this killer middle delt exercise even better.

Almost every image of the cable side lateral you find shows the pulley low, near the ankle. But you’ll get more middle delt load in the phase of the exercise when it’s most important if you raise the pulley a few inches. Put it at knee level or slightly higher, where the cable runs more-or-less straight in front of your body from wrist to pulley.

This higher pulley positioning puts resistance directly perpendicular to the middle delt…exactly where it should be for optimum benefit.

As alluded to earlier, the grip can be the first point of failure during a side lateral, and over-gripping can lead to tendinosis (in this case tennis elbow). So why not take it out of the picture?

Using a wrist strap instead of a handle frees you to concentrate on your shoulder without concerning yourself with grip. The 3” or so of arm lever length you give up is well worth the trade-off.

Any adjustable wrist strap with a carabiner will work. Get one that’s got enough padding to maintain comfort when the weight gets heavier.

Cable behind the body.

We could debate if positioning the cable behind the body adds much to the exercise. However, it may be more comfortable and feel more natural to some lifters.

To perform this variation, the lifter stands in front of the cable. This forces strict abduction to the side without the arm tracking forward at all (since the cable would hit the backs of the legs).

As long as you can perform the side lateral this way without externally rotating the shoulder, this version should work fine for middle delt isolation. Just know that external rotation engages the posterior delt, so it would no longer be a middle delt isolator. If the arm pulls backward, or the palm turns forward, you’re externally rotating and taking the focus away from the middle delt.

No cable machine. No problem.

The Lying Dumbbell Side Lateral finishes a close second to the Cable Side Lateral. Some lifters prefer this exercise to the cable side, saying they feel it more specifically in the middle delt and more intensely in the beginning phase of the movement.

How to do it:

Performing this exercise on an incline is an acceptable tweak. If you’ve got an adjustable bench, raise it to the first notch of incline and do the exercise in the same way described. Or, you can prop yourself up with the non-working elbow.

Just remember that your arm will be perpendicular to your body and not the floor in the finished position.

Removing momentum is a good thing when it comes to isolation training for body part development. Momentum on the other hand is crucial to strength and power training exercises.

Doing a side lateral with support makes sense if you require it to take the momentum out of the mix. The idea is that if you hold onto a sturdy upright of some sort, like a cable machine, the non-working arm is supporting your body so that the upper body and legs can’t get into the act.

No doubt you’ve seen the supported side lateral done with cables (or dumbbells). The exerciser holds onto a support and leans away, causing the working arm to hang straight down at the bottom of the motion and away from the legs. This is also known as the Egyptian lateral raise.

With an exaggerated outward lean, the range of motion is decreased by the degree of the lean. To use an exaggerated example, if you leaned out where your body was 45o to the floor, your side lateral motion would only travel about 35o, which is a paltry range of motion.

The farther you lean, the less your shoulder joint has to move…which means you’re cheating your middle delt.

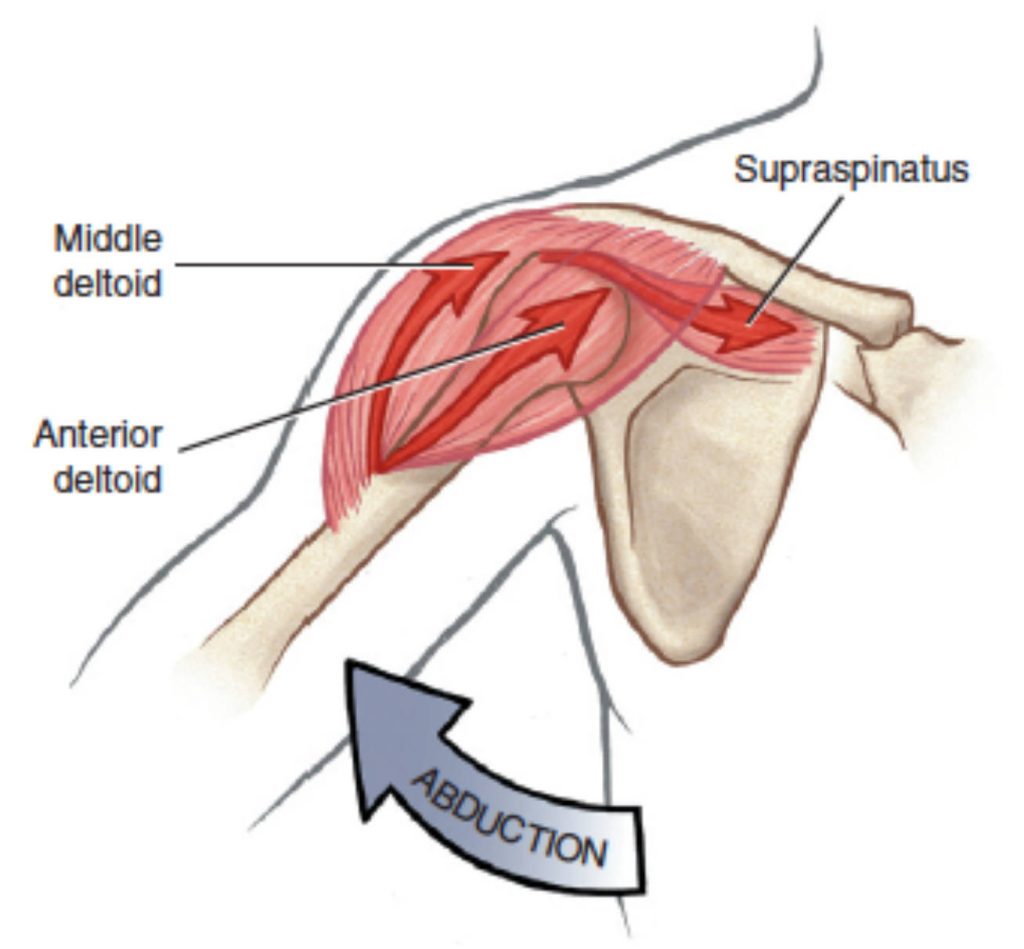

During the traditional (non-leaning) side lateral motion, the medial delt gets help from the supraspinatus, a muscle that lies underneath the bones of the shoulder and deltoid, hidden from view.

The supraspinatus initiates the first few degrees of shoulder abduction by tugging on the head of the humerus, causing it to rotate inward and the upper arm outward. It gets things going for the middle delt which takes over after the first few degrees of movement.

Hypothetically, leaning away from support takes the supraspinatus out of the mix and again—hypothetically—makes the exercise more of an isolation move for the medial delts.

It’s unclear if leaning provides any advantage.

You’re better off betting on a fuller range of motion and not leaning out away from support if you need the support to help prevent you from using momentum.

The classic. Like a delicious greasy hamburger, sometimes you’ve got to have these just because. They’re a throwback to the golden years of bodybuilding. We’ve learned some stuff about lifting science since then, so the exercises featured above are biomechanically better, but the seated dumbbell side lateral is just straight-up satisfying.

How to do it:

If you’d like a little upper trap action at the top, shrug them up beyond parallel—like a high pull—as long as you’re aware of what you’re doing. Adding traps takes the exclusive focus off the medial delts and makes them a compound—not isolation—exercise.

There’s one fundamental downside to the dumbbell side lateral: resistance increases as the arm moves outward. In biomechanical terms, it’s late phase loaded when the muscle is at its weakest.

In general, seek exercises that are early phase loaded to take advantage of a muscle’s natural strength curve.

The standing variation of the seated dumbbell side lateral above.

Very few lifters are disciplined enough to keep their bodies immobile during this variation. Using more weight than necessary, hitching with the knees, and dipping the chest is too tempting. For more effective middle deltoid exercises, the only body parts that should move are the arms.

The seated Side Delt selectable weight machine enables a stable, momentum-free way to isolate the middle delt. The lifter should account for the lever arm (described above) is half what it would be if the weight was held at arm’s length.

No problem. Just adjust the weight to add more to the stack.

By now you may be asking why we’re all over side laterals and not discussing other popular alternative middle deltoid exercises. There’s a scientific reason why.

Side laterals work as well as they do for medial delt development because of physics, and the physics of levers specifically.

When weight is raised at arm’s length using only the shoulder joint to move it, the actual weight that the deltoid must move is magnified by the length of the arm.

Levers are simple machines that help us do work, and our musculo-skeletons include many. Levers include a fulcrum, an effort arm, and a resistance arm. The arrangement of these dictates whether they are Class I, Class II, or Class III levers. One class isn’t better than another, just different.

The shoulder is an example of a Class III lever. In a Class III lever, the effort arm is shorter than the resistance arm. When performing a side lateral, a very short “effort” arm must move a load at the end of a comparatively long “resistance” arm. Let’s create an example:

Let’s say our exerciser has a 30” arm, measured from their shoulder joint to the top of their hand, where there is a 20 lb. weight. The fulcrum is the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint, and the effort arm is the medial delt, which ties in just 1” above the fulcrum.

F = Force

L = Length from Fulcrum

X = Length to Fulcrum

That makes our formula F = (W x X)/L.

F = (20 x 28)/1 F = (560)/1 F = 560

Your middle delt must use 560 lbs. of force to raise a 20 lb. dumbbell.

Now, let’s say the lifter bends their elbow so that the weight is now much closer to the body. The variable inputs to the lever equation change when that happens.

There’s some trigonometry involved for a thorough mathematical expression of bent arm leverage, but in general, the actual load you lift decreases the more you bend your arm. If the arm is bent at 90o as is commonly done in the gym, the load is roughly half what it would be with the arm straight.

To illustrate, let’s create another example.

Let’s say that our hypothetical lifter has watched a YouTube video saying that beast mode weight must be used to build delts now bent their arm to 90o so that they can lift a heavier weight. They’ve selected a bigger weight, 35 lbs., instead of a 20-pounder. And, they bend their arm at the elbow, such that their “lever arm” is now half, or 14”.

Here’s our same equation using the adjusted variables that better suits our imaginary lifter’s ego.

F = (35 x 14)/1 F = (490)/1 F = 490

As you can see, our lifter would be getting more work using 20 lb. dumbbells with arms straight than with 35 lb. dumbbells with arms bent. Not to mention that the lighter weight will likely reduce the temptation to hitch the legs or dip the torso for momentum, and there’s less shoulder wear and tear.

The side lateral delivers max benefit when only the shoulder joint moves. There are two common uses of momentum in the side lateral: Hitching the knees, and swinging the weights.

If there’s waist or knee movement, you’re using momentum.

Use a lighter weight, and let your shoulder be a hinge.

Shrugging takes two forms:

A shrug to finish each rep for some bonus upper trap work is fine in concept, but it turns the medial delt raise into a compound movement. There are better ways to hit the upper traps in isolation. Give your medial delts the attention they deserve and move only the shoulder joint.

Bending the elbows can make the side lateral more comfortable. If you do bend them, don’t bend too much, and keep an eye out for what can happen when there’s too much elbow flexion.

In general, you’re better off not bending the elbows. Three things happen with too much elbow bend, and they all three reduce the benefit of a well-executed side lateral:

Remember, the side lateral is an isolation exercise, designed to work just one of the three heads of the deltoid, the medial head. Because you’re isolating just one head of the muscle, less weight will be necessary for pristine form.

If you were around for Woodstock, you’ll remember the Funky Chicken. If you weren’t, and not exactly a student of pop culture history, the Chicken was a dance featuring hands in the armpits, flapping arms, and lots of bending at the knees.

And, if you’ve been around the gym for a while, you’ve probably seen somebody performing middle deltoid exercises holding the dumbbells (usually way too heavy) with arms completely bent, right up near their armpits. Elbows moving up and down…weights, not so much. Yup. Do the Funky Chicken.

No, don’t do that.

Weights actually have to move for weight training to work. Twisting them at your armpits isn’t lifting.

There’s so much wrong with this butchered version of the side lateral that it’s kind of a waste of time to even get into the detail of why it’s so bad. But we’ve come this far, so here’s a summary:

The side lateral motion in general works in harmony with the way the medial delt is designed, so a strict side lateral motion is best for developing the medial deltoid. You’re using the medial delt in the way it was intended.

Up till now, our discussion has centered on the side lateral and its various permutations.

What about presses?

Overhead presses have been around the iron game for maybe longer than any other exercise. They are so much a part of iron game history that not including them as medial delt builders seems like heresy. The overhead lifts were performed by strongmen, who at the time were the guys with the muscles.

Since those days, gym folks have figured out that feats of strength and muscle building do not need to go hand-in-hand.

The inconvenient biomechanical truth is that overhead presses are not middle deltoid isolators. In fact, the medial delt gets very little action during any type of overhead press.

There are two biomechanical reasons why shoulder presses aren’t good middle deltoid exercises.

If you were to make a case for overhead presses and deltoids, you’d need to argue them as anterior (front) delt exercises.

The anterior delt works during barbell and dumbbell shoulder presses, and Arnold presses. Anterior delt muscle origin and insertion orients it to move the arm overhead when the upper arm is in an overhead pressing position.

The anterior deltoids work against gravity when the shoulders and arms are in a position to do one of these presses, meaning they’re positioned directly against resistance.

There are also better anterior delt exercises than overhead presses. Regardless, overhead presses make more sense for anterior delt hypertrophy than the middle delts.

Let’s put it this way: take two lifters. Have one do only overhead presses. Have the other do only a lateral raise variation. See whose delts get big first.

Those are our picks for top isolated middle deltoid exercises. Because the shoulder joint is a ball and socket, it allows for a wide range of variations of the side lateral.

You have to pay strict attention to form to isolate the medial deltoid. Rotating the arm forward or backward turns the side lateral into an anterior or posterior delt exercise, so you have to concentrate to keep the palm facing down throughout the movement.

Work to perfect the side lateral motion, and put use these medial delt isolators to turn your deltoids into cannonballs.